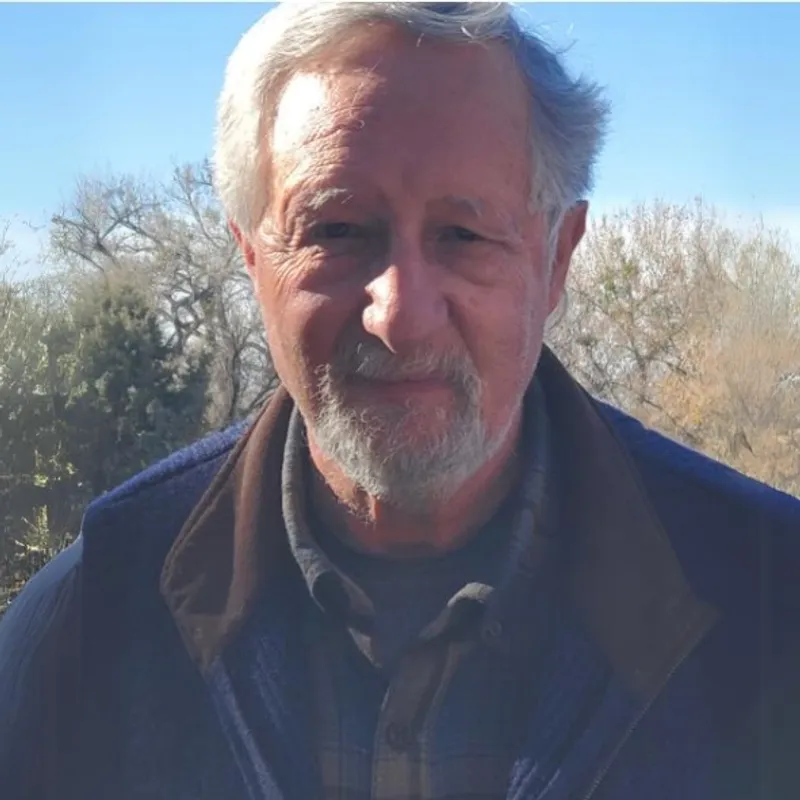

The Founder

Since 1953, Bob Crosby has focused on the application of behavioral and social sciences to organizations and communities. He has consulted with or advised consultants and staffs of several hundred organizations, sharing his expertise in productivity, quality, employee involvement, conflict management, performance measurement, team building, organization/group diagnosis and change management.

His experience ranges all levels of the organization, in diverse contexts, from CEO’s to hourly workers. Usually working with his wife Patricia, he consulted in Russia, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Germany, Italy, Canada, Mexico and Jamaica.

In 1969, he founded the Leadership Institute of Spokane/Seattle (LIOS) from which over 2000 people have received their Master’s Degree. Bob retired from Graduate teaching in 2005 and holds Faculty Emeritus recognition from LIOS, a Distinguished Alumnus award from Boston University, Lifetime Achievement Award from the Organization Development Network and an honorary doctoral degree from Bastyr University in Seattle. In 2005 he became semi-retired and joined his sons in their consulting businesses periodically until he finally retired for good at the age of 90.

Bob’s international and national experience, animated by his deep interest in intercultural work and non-dominant group inclusion, has been and is the backbone for LIOS. His legacy of producing tangible results for organizations, at the intersection of organizational effectiveness, social justice, and performance has allowed his consulting business, along with thousands of

LIOS graduates, to produce unprecedented results.

Bob lives harmoniously and happily with his wife and partner, Patricia, and can belt out an operatic tune upon request.

Q: Tell me about your background.

A: In 1953, I went to Boston University. It was there I had my first T-group. The T-group was invented in 1947, so to go to a university six years later and have access to this practice was highly unusual. At the same time, at Marsh Chapel on Boston University’s campus, Howard Thurman, the Godfather of the Civil Rights Movement, was holding forth. On my first Sunday I wandered into Marsh Chapel and heard Howard Thurman speak. I was stunned, and then spent each Sunday while at Boston University listening to him, and each Sunday evening in a small discussion group with him.

That year changed my life. Several of Thurman’s biographers have said, “If you want to experience jazz, go to a service at Marsh Chapel and hear Thurman!” He was teaching and living authenticity and so was the T-group. These influences blended in my life and practice, and I was profoundly affected!

Just a year earlier, in 1952, I was learning about outdoor education and small group camping and was writing my thesis. Melvin Moody, my leader at Camp Wanake in Ohio, encouraged and funded me to attend a month-long camping experience with L.B. Sharp, a pioneer in small group decentralized outdoor education.

L.B. Sharp was a profound conservationist who was experientially oriented. I lived in a covered wagon in a small group of eight where others lived in a tipi (teepee) and a hogan. He taught us that if you want to get acquainted with a tree, touch it, experience it, don’t just name it. L.B. Sharp was a student of John Dewey, one of the major educational philosophers of the 20th century. I began to realize that I was being influenced by several educators who had been influenced by John Dewey. This was profoundly true also at Boston University School of Theology.

I expected to have a career in outdoor education, and that what I was learning would help me mightily in this. After B.U., I became national staff for the Methodist church where I spent a major part of the 60’s as Director of Camping and T-group training for the national United Methodist Church headquartered in Nashville. I used the T-group and its experiential components to prepare camp counselors to be counselors who knew how to tune into others, lead and ready them for the young campers who were often away from their family for the first time in their lives. (Circa 1960s) I went on to do T-groups all over the states with the Methodist church, while at the same time, getting training at the National Training Laboratory (NTL) by pioneers in the T-group movement such as Leland Bradford, Ken Benne, Ronald Lippitt, and so many more.

I never dreamed I would be a faculty and especially the lead of a graduate program that would graduate a couple thousand students. I modeled LIOS after what I learned at B.U., especially the T-group leader who was my major religious education professor, Dr Walter Holcomb.

All this experience laid the groundwork for what I would do in Spokane.

Q: Who else influenced you?

A: Ron Lippitt, then the Director of the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan, was my mentor for three decades. Ron had been a student of Kurt Lewin. I worked with Ron throughout the late 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s. He helped me design and develop interventions such as the survey feedback work, I did with colleague John Scherer in many major institutions/organizations. John and I sold a survey instrument we created to 600 organizations and trained many of the people in how to lead survey feedback with Ron helping us in the training. Ron often utilized his graduate students such as the later preeminent Richard Schmuck of the University of Oregon, and Charles Jung of Portland’s Northwest regional labs. He helped me design interventions with youth workers in various states across the nation!

In 1969, I arrived in Spokane and decided I wanted my own consulting practice. I named it the Leadership Institute of Spokane. Soon thereafter Gonzaga University asked me to lead workshops. I began to teach a class called group process, which was essentially a T-group. I was also leading retreats. This was a marvelous experience for several years.

Once in Spokane, I became acquainted with the Episcopal Bishop Jack Wyatt. He was a T-group trainer in the Episcopal church. Jack then hired me to work with his priests who were dealing with the fact that some of them were gay. I was a certified sex educator and had done inclusion work with gays and social justice issues. These issues were always at the forefront of what I did and, as a result, Jack became chairman of the first LIOS board.

About three years into running LIOS, students began to ask how they could get a degree. There was great interest at Gonzaga to house LIOS as a Master’s degree but that move did not work out. Ed Lindaman, president of Whitworth University, heard that I was looking to have a Master’s degree and approached me to begin the graduate program there. It was magic! In moments we had a graduate program. We then told our current students and invited others. We had about 50 people interested right away. We were off and running.

Q: What do you think generated all the interest?

A: Interest was generated because the T-group and experiential education was unknown and mostly unheard of at that time. I could generate enthusiasm by sending out mailings (which I did quite often) and just talking to people at various events. People were showing up with little effort from all over the community and the buzz was huge, so the word spread fast.

Carl Rogers was invited to Gonzaga. He was asked to lead encounter groups. I love Carl Rogers, but I thought it was a disaster. He had 100 people on the lawn, and you just can’t do that—the conditions were not right. Plus, many of these folks began to lead a group after one session of preparations—and that’s why I got hired by Gonzaga. I was certified by NTL and therefore the National Education Association. I was called an NTL associate. Many at Gonzaga were concerned about the quality of what was happening.

The other thing that was going on at the time was that Richard Nixon had sponsored a youth training program and there was an approved program in Spokane. I had developed a reputation among the social services agencies by the kind of training I had been doing. Many were interested in this kind of experiential learning. For certain, it was more exciting than the other available programs.

Because of this LIOS got many students paid for by the state. In fact, administrators from GU, WSU, and Eastern Washington held a meeting to try and understand why students were not using the funds to go to their school and instead were going to LIOS.

Ultimately, Whitworth got a new president who was not aligned with our values, so LIOS moved to Seattle.

Q: When you invited Ron Short and John Scherer into the process, what was your vision?

A: When Whitworth invited us in the program, I needed faculty. Ron was a prime candidate because he taught at Whitworth, but he was not happy. He had recently attended his first T-group and when he learned about my work, we got acquainted right away. He came to visit me in my home. Ron has a PhD in psychology and provided a theoretical background that I didn’t have.

John was in a conflict lab in Green Lake, WI. I received feedback from the leader that John was a problem and was asked to “help.” So, I sat in and witnessed the process. What I saw impressed me. John was getting a lot of push back yet interacting at a high level, not swallowing the feedback but truly trying to learn from it. I was very impressed, pointed to John and said, “You’re great,” and proceeded to give him very specific feedback that I believe he liked. My trainer was upset with me because she was saying the opposite. Well, it wasn’t long before I asked him to join me as faculty.

Ron, John and I were a great team.

Q: How did you grow the program?

A: We built LIOS in Spokane. John was a great marketer; he would get people excited. We drew students from Spokane, Hanford, and an army base on the coast.

Tragically around 1981, Ed Lindeman passed. Whitworth got a new president who was not aligned with our values. So LIOS moved to Seattle. This was the beginning of LIOS finding other schools to affiliate with. When we eventually moved to Seattle, we picked up two staff, Brenda Kerr and Denny Minno. Brenda later was the greatest president we ever had; she eventually grew LIOS to over 400 students.

Beyond the program for the public, LIOS also had about 10 years of amazing work in the Alcoa organization. We were not an official program, but more grass roots. We graduated about 300 leaders, including many steel and electrical union workers. The corporate graduate program came into being because Dom Simonic, a manager at Alcoa and I were working together. He wanted people to be able to do the types of things Patricia and I and Tom McCombs, a graduate working at the Addy plant where Don became manager, was doing in his plants. He asked for a corporate master’s program and much to my surprise, when I mentioned it to Brenda she said, “great let’s do it!” Just like that we had a corporate program.

Many graduates of the corporate program quickly vaulted into high level leadership positions including some, within a few years becoming CEOs.

Q: What stands out for you considering your large body of work?

A: My dad was a steel worker. So, I have always connected with all levels in any plant. Unlike many consultants, I made sure that my work went throughout the plant and involved work with the people at the lowest levels. I know that for real change to happen, transformation must happen throughout, and trust must be developed at the lowest levels, or it won’t work. Therefore, when I started at some of my most difficult scenarios, including plants with Unions where the workers in the past, had literally been held out of the plants with guard dogs and security guards, I would ask to get a plant tour with an hourly union employee working the toughest job in the plant. Then I would focus on connection and understanding. This strategy paid off and was critical for me. At one kick off for a multi-million dollar project, the union leader introduced me to the employees by saying, “this is Bob Crosby, he is one of us, he is a member of Union 234!,“. That is the type of support needed to impact real change.

I also connect with people that are struggling and who others find, “hard to deal with.” It is vital for me to honor that all of us have pain, and that many have never been truly listened to. So, my job is to honor and connect while honoring all points of view yet ensuring that the process and improvement goes forward. A great example of this was how I worked and connected with Pierino. He was an hourly worker in Fusina, Italy. The history of the plant was contentious. The government had previously run the plant. There were three unions and Alcoa bought the facility. We were about three weeks into the engagement, when all the managers and employees had a meeting; the room was packed. The plant manager made a statement, then he called on me. I saw one guy waving his hand furiously.

Pierino was frantically waving his hand. I acknowledged him and he said with a strong voice, “How do you expect us to trust management!? They’ve treated us badly for years!” I replied saying, “Thank you for asking that. I’m sure many are wondering that in this room right now. I don’t expect that. As you know, trust takes time to develop. Again, thanks for saying that.” Several times he again voiced accusations with a strong (hostile?) voice. Each time I responded thanking him for bringing up whatever he did. I looked for the kernel of truth in each statement, did not defend, and retained control until the atmosphere had cooled.

I have run into many people like Pierino over the years and the same things happened often during community development work. No matter how hostile folks were, I’d thank them and acknowledge and honor their point of view. This is a profound and simple acknowledgment that moves people and groups. There are a few chapters in my “Memoirs of a Change Agent”, that point to this work.

We had so many wonderful opportunities. For two years, while working at the Fusina plant, we lived in Venice, Italy. We also lived in Tuscany, in Russia, did a training in Ukraine, did a lot of work in Mexico where people came from all over South America, and worked in Canada. We lived in Philadelphia for two years and helped PECO energy with turnaround.

We’ve had a rich, rich life.

Q: Why does the LIOS restart matter?

A: I’m in contact with many of my colleagues and still, to this day, no one does what we do. We embody social justice issues and are advocates for non-dominant cultures. We do organization development the way Kurt Lewin intended— with action research, down through the organization. You just have to care about people. Others can teach important things, but they don’t bring what we bring.

First Faculty & Collaborators

Ron Short: Feedback as Mutual Inquiry is Essential

Ron Short received his doctorate in psychology from Claremont Graduate School in 1965. He was an intern with the National Training Laboratories in 1969 and co-created the LIOS Master of Arts in the Applied Behavioral Sciences in 1973. He co-created The Leadership Group in 1988.

He is currently the founder of Learning in Action Technologies, a firm that helps coaches and consultants, use Emotional Intelligence that measures, concepts and skills in their practice.

We spoke to Ron about co-creating LIOS.

Q: Tell me about the spark for creating LIOS.

A: It was the late 60s and early 70s. I started out in the navy and had worked at the IRS, where I met Bob Crosby. I also taught at National Training Laboratories. It was around this time where I experienced the T-group for the first time and became convinced of its power as a teaching model.

I was at Whitworth University teaching psychology in their graduate school when I got a call from the department chair telling me that Bob Crosby was starting a new program. Then, I got a call from Bob. He wanted to use the T-group model as the basis for the program and that was terribly exciting for me. These were the values I wanted to be a part of.

Bob was at Gonzega University, in Spokane, WA, seeking to build a new master’s program. I eventually moved back to Spokane to help co-create the program. This became my teaching niche.

Ed Lindaman, President and future thinker, of Whitworth College in Spokane, Washington invited LIOS to become a Masters of Arts in Applied Behavioral Sciences. LIOS accepted and became a contract program at Whitworth.

Q: What was your most stand-out memory?

A: I worked as faculty with LIOS from about 1973 – 1989. We had winter and summer programs with cohorts of about 30 people.

I was tenured faculty at Whitworth and eventually taught primarily with LIOS. After all these years, and a lot of learning, I would say that LIOS was about learning while you’re living life. Learning in the now moment and learning in relationship. We later discovered the hard skills that accompany this kind of in-the-moment learning. I call this “inside-out learning.” I went on to develop the EQ Profile, with my wife Jan Johnson, and we built Learning in Action Technologies. The work was all related.

There were many studies about the T-group. With that said, each group was unique and every leader was unique. The whole process really shaped my questions and inquiry. John Wallen, a social psychologist, was the thought-leader who I learned from. Based on his work, we were able to bring these skills into the T-group process. His insights were incredible. The T-group model facilitated real change.

There was a study in 1946 studying racism. I realized that in this study people were talking about what was going on inside of them. There were many T-groups at that time that were not skilled based. John Wallen brought in this powerful insight so that the LIOS program was able to include core leadership skills, such as listening and descriptive skills, versus other types of T-groups that were more personal development based. The Wallen skills honored leadership and authority in an organizational system.

I remember the rush of developing LIOS from scratch. John, Bob and I sat under the plum tree in Bob’s yard. We sat with no agenda and created out of fresh cloth. I was thrilled when the first cohort came back! And, and they kept coming back! It was thrilling to see this work in action. We improved as we went along and fed off the student’s motivation.

Q: Why does the restart of LIOS matter?

A: As a psychologist, one of the things that had always troubled me was that psychological domain is mostly about self-inquiry and individual development. There is an absence of what goes on in relationship. If you think about the skills and the context it takes to develop relationship, these skills directly impact community—and our ability to form and work in community. Every one of our cohorts naturally created community.

We did not collect data in this area, but I think the community development happened due to the skills we taught. There’s a misnomer about democracy. Many people think that democracy is simply about allowing a group to do its thing. This notion is not true. It’s important to recognize authority. There were plenty of T-groups that flailed around. I remember a pastor standing in front of his congregation after a member had passed away and asking the congregation what they should do. This is not leadership.

To be democratic you need authority to manage processes. The Wallen skills are key to managing with authority that exists. The T-group process plus the skills teach competencies for democratic leadership.

Feedback as mutual inquiry is also essential. Yet, its complex. Mutual inquiry is learned with a leader leading. You can’t just throw out authority. You need it to shepherd the process.

Our students came in as strangers and they walked away as a community – not by chance. They learned skills that can be replicated.

(circa late 1960s) John and Bob in the early days, learning experientially while building the LIOS program.

John Scherer: The Conflict Lab Changed my Life

Since 1982, John has contributed around the world as a leadership and organization development consultant, author, and speaker. His mission is transforming the world at work via unleashing the human spirit. In 1982 he founded Scherer Leadership Center (SLC) to scale this mission of assisting leaders to transform their lives and their organizations.

The work has taken him to China, Africa, Poland, The UK, Canada and New Zealand. He’s written, “Work and The Human Spirit” and, “Five Questions That Change Everything.”

He has four amazing grown children and lives in Seattle, WA and Warsaw, Poland, where he runs or swims and does yoga daily. He still plays the guitar and performs the occasional magic show.

Q: What brought you to this work?

A: I was called out of the priesthood and into this work. I was the 4th generation of Lutheran pastors, on my paternal side. In 1971 I was the Lutheran chaplain and senior pastor at Cornell University. During my internship, I had had a National Training Lab (NTL) T-group experience that piqued my interest. There was a workshop in Green Lake, WI and there were a number of tracks; we called them Labs back then. I filled out a questionnaire and it said, you might be suited for the conflict lab. Well, it changed my life.

The way I knew this work was for me, is that I experienced the work, like I already knew this work. Then, Bob Crosby confirmed that I was a natural. I went on to work with Bob as the first faculty and we just swam together.

In 1973, my wife had had a life changing experience and ultimately, we made a decision to split. The very next day, Bob called me and told me about his idea to begin a graduate program. Shortly after that I (left ?) and took off to Spokane, WA. We sat in Bob’s backyard for three or four months, with a blank slate, designing the graduate program.

What a team! Ron (Short) held the academic rigor. Bob and I were coming from a laboratory environment. With my gestalt backgrounds, I came up with the Pinch Theory and the Waterline model that are still taught today.

Q: Tell me about the spark for creating LIOS.

A: Ed Lindeman, the president of Whitworth college at that time, and his leadership team, were ripe for a new program. We had the opportunity to form the applied behavioral science master’s program, as laboratory learning. It was the first of its kind, probably in the world. Instead of going to the library, we created an experiential format. In 1973, we were doing video feedback!

The first couple of years, the network was based around Bob and Ron’s networks in the Northwest. Then, I was invited to Ft. Lewis, the army base south of Seattle. At the end of the program, I casually introduced our new grad program. About 20 people expressed interest – 75% of the group. I went back to Ron and Bob and let them know that I thought we had something. From there we build a summer program and LIOS took off.

This experience was the highlight of my career.

Q: What made it the highlight? What are some standout memories?

A: Working with Bob and Ron, a blank slate and the ability to contribute our unique “genius” (that particular combination of strength, natural talent and trained focus) was wonderfully exciting. Secondly, it took my whole self. I brought everything I was to the moment, every moment, calling on my mind, body, spirit to be present every moment. Lastly, to see the results and life changing experiences that took place was priceless. I was a therapist and had helped a lot of people, but to see the incredible changes layered with the added theories and skills was… I’m just grateful.

Q: What did you most hope for?

A: The truth is that in the beginning, I just wanted to do what Bob was doing. He was a hero and mentor for me. I remember my first T-group and having an awareness that I was experiencing, really experiencing what we were teaching in seminary. If I had experienced the T-group before I went into seminary, I might have just skipped that part.

Q: Were you thinking about organizations or leadership work, at this time?

A: I was doing transformational work with individuals and I felt grateful to be in the room. Then, I realized that whomever they were talking about should also be in the room. It’s the concept of the whole system. I would say, “Your husband should be here, let’s get him in the room.” I would have an empty chair, but then I finally realized I should invite that person into the conversation.

Once I had a couple bring their dog. I learned about Virginia Satir and her (first) book, “Conjoint Family Therapy.” Intuitively I knew this systems piece was a big part of organizational systems.

When I was in the ministry, some folks were business people. I was asked to do conflict interventions. By the time I left the ministry, I had one day per week that I could practice team building and the kind of practice I was learning.

Q: As you created the school, what were you imagining?

A: That the ways of interacting and the skills could be taught. And that people could get academic credit for it. It was equal to chemistry or any other area of formal study.

Q: What was it like to be faculty?

A: Exciting, Rewarding. Scary. Challenging. I knew I was living out my purpose every day. Even after the second year, as the curriculum got clearer and clearer, but doing laboratory learning, you didn’t know what will happen. You needed to be ready for all kinds of things to happen.

[Story about the marketplace. Women barricaded on 2nd floor…Not going to relinquish power.]

Q: What is trauma informed?

A: Twice a year, I get to work with 40 men and women, in Krakov, from all around Poland, in a competitive process. They come together for 7 days and its intensive experiential work. This past time we had participants pushing back. One woman literally threw her book in the middle of a session and exclaimed that we were manipulating the group.

I used essential LIOS skills to address her concerns. We sat down on a bench and talked for about 2 hours. I really got on her side and empathized with her. I simply asked if she would be open to anther possibility. In the end, she gave me a big hug. When I followed up with her she told me, “You didn’t defend yourself. You didn’t try to talk me out of my experience. You just invited me to consider another possibility.”

When people are resistant, they do not feel safe. They are not wrong or a problem, they are holding a space in the field. Fear and manipulation are also in the field. We, managers, the authorities in the system, need to be real and honest with people. Its an Akido, of moving with the energy that is present. I don’t resist it, but rather I go with it and look from your perspective. Take what is present and explore it together.

Q: What’s your proudest moment?

A: The summer program comes to mind. I can see the love. That’s what moves me. Fundamentally our job is to love people, not to change them. Love them and they will change. When people are in a safe environment and they are being provoked in a graceful and way, good things happen. Being alive together is powerful.

(circa late 1960s) John and Bob in the early days, learning experientially while building the LIOS program.

Douglas Cohen: Foundation To My Successful Career

I was trained as a facilitator in dream psychology and was running adult-learning dream study groups in Seattle, and then through the University of Washington. I was also a tennis player and tennis teacher, when one of my students told me about the LIOS program. I joined the LIOS program to add to my skill set. At this point, I didn’t know much about Applied Behavioral Science degree, yet my experience in adult learning and the helping professions was a natural fit for leadership and organizational development. I took to the program like a fish to water. The program was so well done. I admired the skills of the faculty and the dynamism of the program. All the professors were high quality.

Within the next year and a half or two after graduating the program, I learned that one of my predecessors was hired by AT&T Bell Labs. Through my LIOS networking I got my first OD position at AT&T Bell Laboratories in Management Development and Training. Later I joined a network of practitioners, as a junior laboratory facilitator, and continued to work in corporate settings.

Ron Short and his LIOS peers were embedded in the National and International OD network. The first time I went to a session, Ron Short presented. I attended as a young consultant which led to my exposure in this community of practitioners. I was invited into the community and was able to eventually be a presenter in this network. Going from a participant to a presenter was a significant stepping stone in my career.

I consistently drew on the LIOS core models and skills throughout the decades. With leadership and organizational skills, a network, and great opportunities, I was able to establish a practice of delivering management and executive training, one on one coaching, and a specialty as a facilitator/designer for board of directors’ retreat learning experiences.

LIOS helped me assess and address organizations’ leadership and system’s needs. I was able to see and assess the system and help leaders and organizations grow at their learning edges.

LIOS was remarkable: the skill building, the tools, and the professors. It was unquestionably and wonderfully foundational for the success of my 45 years as an international and national OD and leadership consulting career.

Thank you LIOS for much success and career fulfillment.

~Douglas Cohen, Retired Tennis Teacher, Dream Therapist and International Organizational Consultant, LIOS ABS Master’s degree, late 1970s taught by the early original set of professors